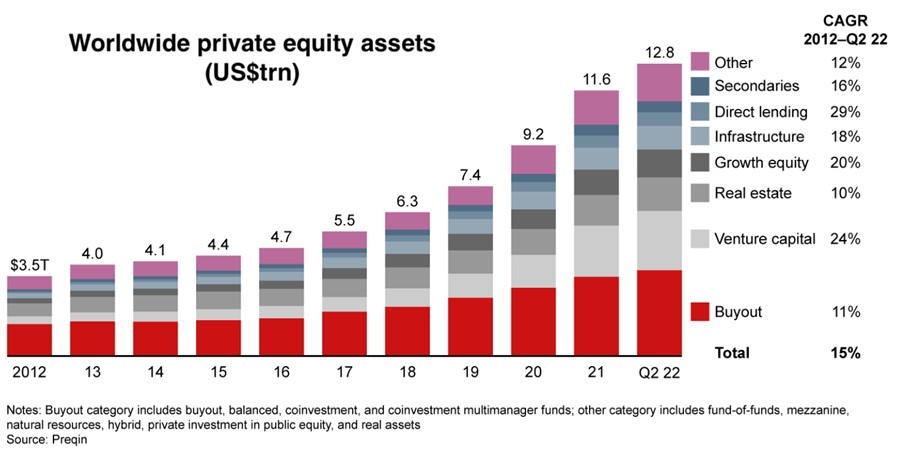

If you are a young professional with an interest in finance, you cannot have failed to notice the rise of private equity investing over the last decade.

Although this exceptional growth has slowed over the past 18 months or so, the total remains more than twice the $5.2 trillion represented by the world’s hedge funds. What does it take to launch your career in this fast-moving industry?

Plenty of choice

The first point to note is that private equity is not monolithic. It covers every stage of the corporate life-cycle from start-up to initial public offering (IPO), with a correspondingly wide variety of portfolio management companies, types, and styles.

It is, therefore, much more fragmented than public-equity investment, with a multitude of small firms. Even the largest, Blackstone, Inc., in the USA, has assets under management that are barely one-tenth those of the US$9.3 trillion managed by BlackRock, Inc., the world’s biggest investment manager of any type.

These characteristics give the career-hunter a variety of options. Big firm or small? Early-stage – venture capital, for example – or late, such as leveraged buy-outs? Big firms offer a greater variety of career paths and look good in your resumé when you want to seek further opportunities. Small firms are quirkier; many have fewer than 10 employees and, although that makes them harder to enter, they can offer a steeper learning curve than the behemoths, as well as a quicker route to greater responsibilities.

Early-stage managers, including venture capitalists, are like incubators; they play a hands-on role in guiding their portfolio companies to growth and an IPO. Usually, they have board representation, help with recruitment of key personnel, and advise on business strategy. All of that requires analysts who are also visionaries with a solid grasp of business management.

Late-stage strategies, in which leveraged buy-outs dominate, are different. They are deal-driven, so their need for diligent research and analysis is bolstered by a requirement for skills in business negotiation, balance-sheet management, and legal drafting.

The main requirements

At very least, therefore, whatever stage is of most interest to you, you need a degree in an analytical subject, such as finance, accounting, statistics, mathematics, or economics. A law degree could also be useful.

However, most firms, especially the smaller ones, hire people at associate level. In addition to your degree, therefore, they will expect you to have some experience in an activity that’s associated with their business, or in one that complements their existing team’s collective skills. The best experience is likely to be a couple of years spent as a securities analyst with a reputable investment bank, or with a business strategy consultant, or as a lawyer with a firm that specialises in company law or financial contracts.

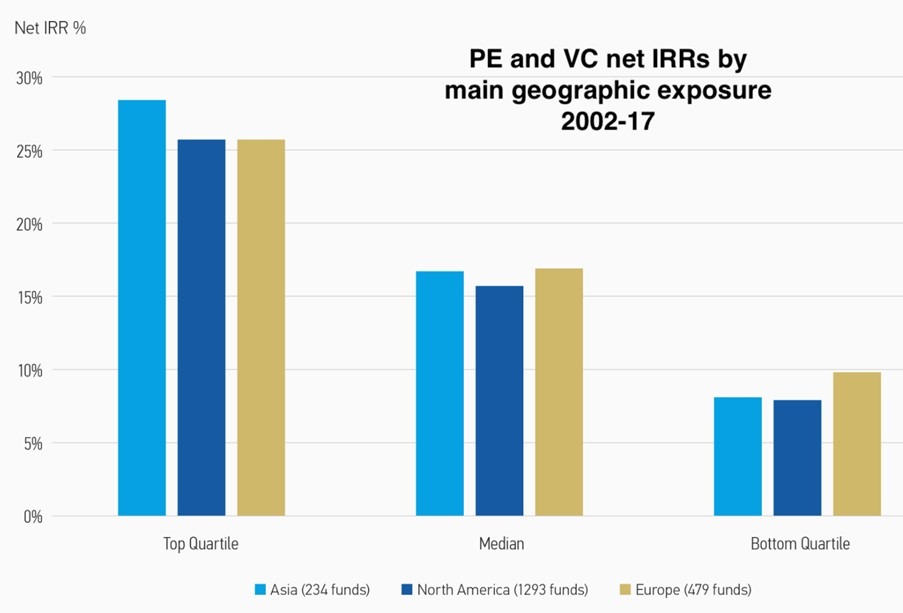

Perhaps, you have a special interest or skill that makes you stand out? For example, a facility with languages, deep knowledge of a specific industry or technology (currently, AI, greentech, and biopharma are in demand), or of the corporate or investment landscape of a particular country. On the last point, Asia is an active area of industry interest right now.

Source: Morgan Stanley

Above all, you will need to be obsessed with details, as well as having a love of problem-solving and rigorous analysis, digging ever deeper to unearth the pertinent facts about a company, country, or industry. The ability to build detailed financial models and business plans will be essential. A facility with the appropriate tools for this – Bloomberg, Excel, FactSet, and so forth – will also be needed, therefore.

Working life and career path

Having secured a role in private equity, what sort of working life is in store for you? Certainly, it will entail long hours – 60 or 70 hours per week is more-or-less normal – and, especially when closing deals, even your weekends may have to be sacrificed, along with your social life.

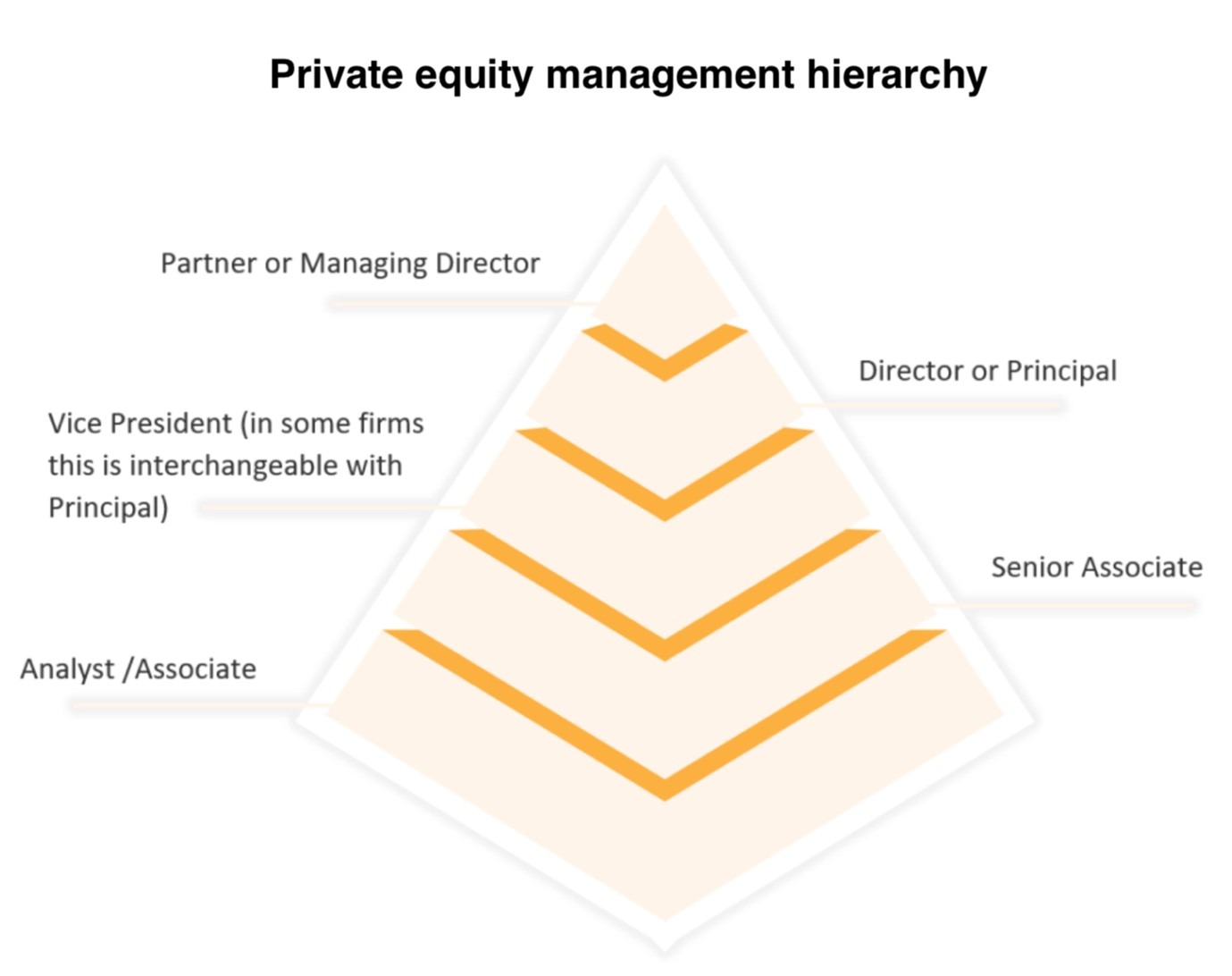

On the plus side, you will work closely with colleagues, even the most senior and experienced ones, so you won’t be just an office grunt, relegated to a corner and forgotten while you update mailing-lists and take messages. On the contrary, small or large, private-equity firms have a relatively flat management hierarchy. Walk into a meeting and you might find it hard to distinguish who is the boss. There are titles and responsibilities, of course . . .

Source: Executive Resume Writers

. . . but they mean little in terms of the day-to-day work. Everyone is expected to be an active participant in, and contributor to, whatever deal is in progress. Even as a newbie analyst, the details you unearth and the personal contacts you make in so doing could be crucial to the success of a transaction or the development of a portfolio company. Your opinion has weight.

Nonetheless, as an analyst/ associate, your time will mostly be taken up with industry and company research rather than dealmaking. Mostly, that will entail reviewing industry research by third parties such as investment banks and management consultants, looking for investment trends and opportunities.

You may need to travel to meet executives at potential investee companies or seek information on legal, fiscal, or political developments in particular regions or countries. Very likely, you will also have responsibility for monitoring the progress of portfolio companies, writing periodic memos and reports on them for your firm’s investment management team.

After two years or so with smaller firms, but much longer at the majors, you can expect to take on wider responsibilities. Having been, in effect, an assistant in your firm’s investment process, you might now be involved in, or even lead, taking a deal from start to finish.

Again, after a few years, you could be made a vice president. That will mean less analysis and research because your responsibilities will include managing relationships with portfolio companies, negotiation with prospective investee companies, and assisting with fundraising activities.

The latter task is the main responsibility of a private-equity firm’ directors. Consequently, they also take charge of relationships with limited partners (investors), as well as having general management duties such as finance and accounts, business planning, and marketing. There may also be a legal role, preparing agreements with service providers such as banks, lawyers, and auditors or, in many countries, overseeing the firm’s compliance with industry regulations.

Finally, there is partnership. Partners a represent their firm to third parties, whether those be service providers, prospective or actual portfolio companies, regulators, and, above all, the limited partners invested in the firm’s fund or funds. A partner will also have to commit a portion of their personal wealth to the firm and its funds. This is sometimes known as ‘eating your own cooking’.

Show me the money

All of which leads to the final and, for many seeking a career in private equity, the main question: how much money will you make?

The table, below, is the broadest and simplest of guides and refers to the USA only. Remuneration in Europe and elsewhere is usually lower. Even so, the career progression is typical, as is the amount of increase in salaries and bonuses with each career step.

| Position | Typical age | Base salary & bonus | Share of carry |

| Analyst | 22-25 | $100,000-150,000 | None |

| Associate | 25-28 | $150,000-250,000 | None |

| Senior associate | 28-32 | $250,000-400,000 | Small |

| Vice president | 32-35 | $400,000-500,000 | Medium |

| Director | 35-39 | $500,000-800,000 | Large |

| Partner | 39 + | $800,000-2,000,000 | Major |

Perhaps, ‘share of carry’ requires explanation. Private equity managers earn a fixed annual fee, usually 2% of assets under management in the firm’s fund, or funds, but also enjoy a carried interest, or carry. Usually, this is set at 20% of the profits made on fund investments, paid when those profits are distributed to investors.

However, sales of investments only happen after a long period, perhaps, as many as eight or ten years. The carry is a single payment, therefore, shared among the eligible members of the management team according to their seniority.

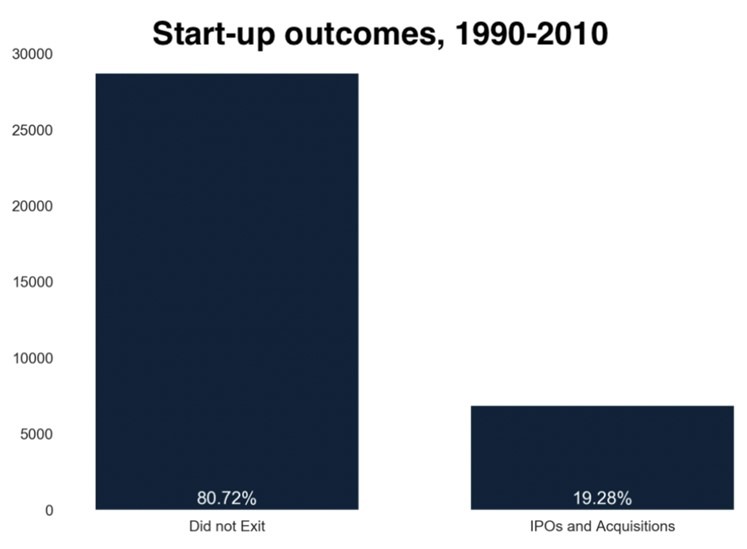

Finally, while anticipating eagerly the riches you can earn in private equity, you should also be aware that this is a high-risk industry. This is especially true of early-stage strategies, including venture capital in particular. Although the post-2010 boom improved the ratio of winners, those good times have faded and the chart, below, is likely to reflect the current state of affairs fairly accurately, with some eight out of every ten investments failing to turn a profit.

Source Medium.com

On the other hand, that high level of risk, along with the long hours of work expected of every private-equity employee, is why the business is so remunerative.

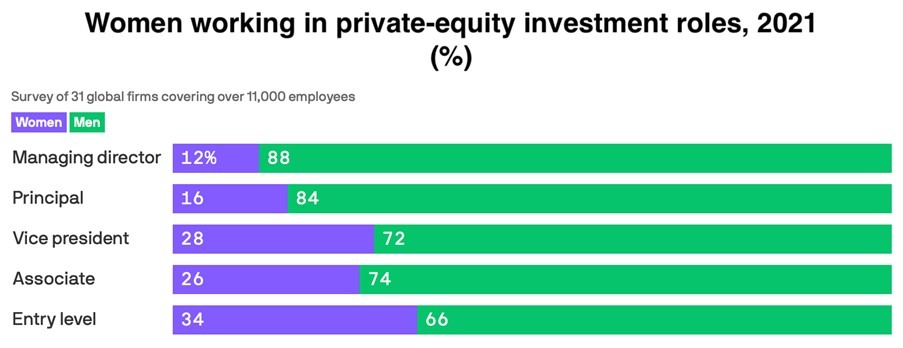

In short, private equity is not for everyone. You need to be curious, dedicated, extremely hard-working, and not a little brave. It also helps to be male, although that is changing.

Source: Axios

The chart shows that women have the greatest representation in the middle and lower tiers of management. One may hope this indicates that, in future, they will rise up through the ranks and take a more prominent part in the industry.

Good luck!